Introduction: Decoding the Competitive Landscape

In the world of economics and business, the concept of market structure is fundamental. It is the framework that describes how firms are organized and categorized based on the type of goods they sell and the nature of competition they face.1 Understanding market structure is essential because it profoundly influences how businesses behave, how prices are determined, how efficiently resources are used, and ultimately, the strategic decisions available to any company leader.3 It is, in essence, the economic environment in which a business operates.5

These structures are not random; they are classified based on a core set of characteristics. The most critical determinants include the number and size of firms in the market, the degree of product differentiation (whether products are identical or unique), the ease with which new firms can enter or exit the market (known as barriers to entry), and the amount of information available to both buyers and sellers.2 Together, these factors define the competitive landscape.

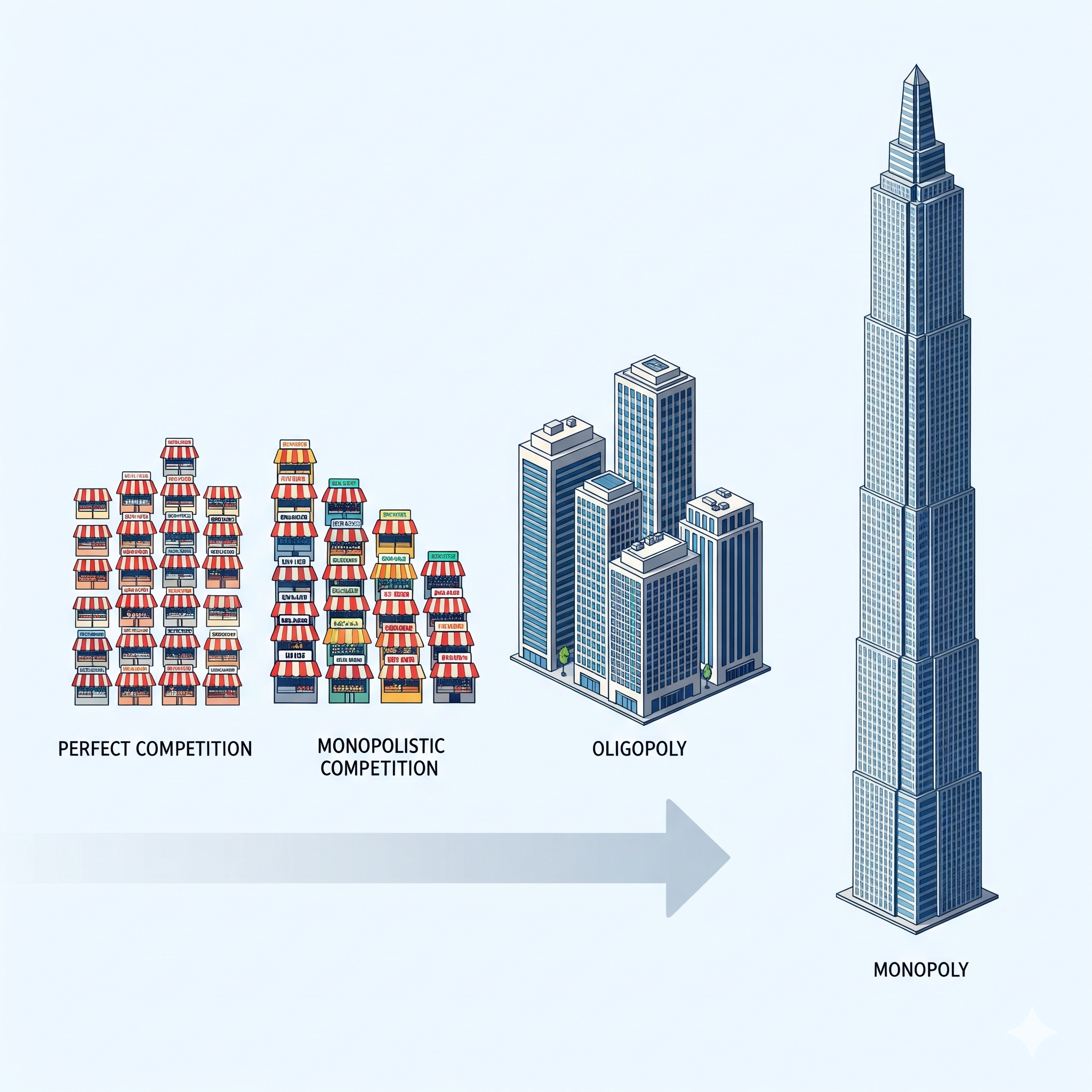

It is helpful to think of market structures as existing along a spectrum of market power. At one end lies perfect competition, a theoretical ideal where countless small firms compete with identical products and possess zero power to influence prices. At the opposite extreme is monopoly, where a single firm wields complete market control.5 In between these poles lie the more common real-world structures:

monopolistic competition, characterized by many firms selling similar but differentiated products, and oligopoly, where a few large firms dominate the market.3

A powerful way to conceptualize this is to view a market structure as the “operating system” (OS) of an industry. Just as a computer’s OS sets the fundamental rules and environment within which all software applications must function, a market structure provides the foundational rules of competition. A firm’s strategic choices—its pricing, marketing, and production decisions—are like applications that must be compatible with this underlying OS. A strategy that thrives in a monopolistic environment would fail instantly in a perfectly competitive one. By understanding this “operating system,” we can better analyze and predict the behavior of firms and the outcomes for consumers within any given industry.

Perfect Competition: The Theoretical Benchmark of Efficiency

Perfect competition represents a theoretical benchmark, an idealized market structure that, while rare in its purest form, serves as a crucial standard for measuring the efficiency of all other market types.4 It is defined by a precise set of conditions that result in the most efficient allocation of resources possible.

Defining Characteristics

The model of perfect competition is built upon four rigorous assumptions:

- Many Small Firms, Many Buyers: The market consists of a vast number of buyers and sellers, each so small relative to the overall market that no single participant can influence the market price or total output.9 Each firm is, as one source describes, like a “drop of water in an ocean”.10

- Homogeneous Products: All firms produce and sell a completely identical, standardized product, often referred to as a commodity.11 From the consumer’s perspective, there is no difference in quality, features, or branding between the products offered by various sellers.8 This means competition can only be based on price.

- No Barriers to Entry or Exit: Firms can enter or leave the market with complete freedom, facing no significant legal, technological, or financial obstacles.11 This free mobility of resources is the critical mechanism that governs the market’s long-run behavior.14

- Perfect Information: All market participants—both buyers and sellers—have complete and immediate access to all relevant information, including prices, product quality, and production techniques.11 This transparency ensures that decisions are rational and prevents any single entity from gaining an unfair advantage.8

Price and Output Determination: The Life of a Price Taker

In a perfectly competitive market, the price is determined by the collective forces of market supply and market demand. The individual firm has no control over this price and must accept it as given; it is a price taker.12 Consequently, the demand curve for an individual firm is perfectly elastic—a horizontal line at the market price.15 This means the firm can sell as much as it wants at the prevailing market price, but if it tries to charge even slightly more, its sales will drop to zero as consumers switch to competitors.12

- Short-Run Equilibrium: To maximize profit, a firm will produce at the quantity where its Marginal Cost (MC) equals its Marginal Revenue (MR). Because the firm is a price taker, the price (P) it receives for each unit is constant, making its marginal revenue equal to the price. Therefore, the profit-maximization rule simplifies to producing where $P = MC$.14 In the short run, a firm can experience one of three outcomes:

- Supernormal Profit: If the market price is greater than the firm’s Average Total Cost (ATC) at the profit-maximizing quantity ($P > ATC$).

- Normal Profit: If the price equals the average total cost ($P = ATC$). This is also known as zero economic profit.

- Loss: If the price is less than the average total cost ($P < ATC$). The firm will continue to operate in the short run as long as the price covers its Average Variable Cost (AVC). If the price falls below AVC, the firm will shut down to minimize its losses.18

- Long-Run Equilibrium: The freedom of entry and exit dictates the long-run outcome. If existing firms are earning supernormal profits, the allure of this profitability will attract new firms to enter the market. This influx increases the overall market supply, which in turn drives down the market price. Conversely, if firms are incurring losses, some will exit the market, decreasing market supply and pushing the price up.11 This adjustment process continues until the market price settles at a level where firms earn only

normal profit (zero economic profit). This long-run equilibrium occurs when the price is equal to the minimum point of the Long-Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve, resulting in the equilibrium condition: $P = MR = MC = \min ATC$.8

The Pinnacle of Efficiency

Perfect competition is considered the ideal market structure because, in its long-run equilibrium, it achieves two types of perfect efficiency:

- Productive Efficiency: This occurs when goods are produced at the lowest possible cost per unit. In the long run, perfectly competitive firms produce at the minimum point of their average total cost curve ($P = \min ATC$). This means there is no waste of resources in production.21

- Allocative Efficiency: This is achieved when resources are allocated to produce the mix of goods and services that society most desires. This happens when the price consumers are willing to pay for a good (which measures its marginal social benefit) is equal to the marginal cost of producing it (which measures its marginal social cost). In perfect competition, firms produce where $P = MC$, ensuring that society’s costs and benefits are perfectly aligned.13

Real-World Proximity

While no real-world market perfectly meets all the strict conditions, some come close. Large agricultural markets, such as those for wheat or corn, where numerous farmers sell a standardized product, are often cited as the closest examples.4 Other examples include foreign exchange markets and certain online platforms selling identical goods.8

The true value of the perfect competition model in modern economics, however, is not in its ability to describe reality. Instead, it functions as an essential diagnostic tool. It provides a “perfectly healthy” benchmark of maximum efficiency. By comparing real-world market structures—with their various imperfections—to this ideal, economists can measure the degree of market failure. It allows for the quantification of inefficiencies, such as the deadweight loss caused by a monopoly or the excess capacity in monopolistic competition. Its primary function is not descriptive but diagnostic, providing the yardstick against which all other markets are measured.

Monopoly: The Power of a Single Seller

At the opposite end of the competitive spectrum from perfect competition lies monopoly, a market structure defined by the presence of a single seller that dominates the entire market for a particular good or service.26 This absolute control grants the monopolist significant power to influence prices and output, leading to outcomes that are starkly different from the competitive ideal.

Defining Characteristics

A monopoly is identified by several key features, with the most critical being the barriers that prevent competition:

- Single Seller: By definition, a monopoly consists of one firm that is the sole producer in its industry. For practical purposes, the firm is the industry.26 Regulatory bodies may use different thresholds; for instance, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority considers any firm with over 25% market share a “working monopoly” and one with over 40% a “dominant firm”.29

- Unique Product: A monopolist sells a product for which there are no close substitutes.26 This lack of alternatives makes the demand for the product relatively inelastic and gives the monopolist substantial market power.26

- High Barriers to Entry: This is the cornerstone of a monopoly’s power. Significant obstacles prevent potential competitors from entering the market and challenging the incumbent firm. These barriers can take several forms:

- Natural Monopoly: This occurs when extreme economies of scale make it more efficient for a single firm to supply the entire market. The high fixed costs of infrastructure, such as in public utilities like water and electricity, mean that one large firm can produce at a lower average cost than multiple smaller firms.4

- Control over a Key Resource: If a single firm owns or controls a resource that is essential for production, it can prevent others from competing. The historical dominance of DeBeers in the diamond market is a classic example.6

- Legal and Government Barriers: The government can create monopolies by granting exclusive rights through patents, copyrights, and licenses. These are intended to incentivize innovation by protecting intellectual property but result in temporary monopoly power.6

- Strategic Barriers: These can include high initial setup costs, aggressive pricing strategies, or control over distribution channels that make it prohibitively expensive or difficult for new firms to enter.6

Price and Output Determination: The Art of the Price Maker

Unlike a firm in perfect competition, a monopolist is a price maker. It faces the entire downward-sloping market demand curve, meaning it can choose any price-quantity combination along this curve.33 However, it cannot choose both price and quantity independently; to sell more units, it must lower its price.35

This relationship has a critical implication: for a monopolist, Marginal Revenue is always less than Price ($MR < P$). When the firm lowers its price to sell one more unit, it must also lower the price for all previous units it could have sold at a higher price. This causes the marginal revenue curve to lie below the demand (Average Revenue) curve.32

- Profit Maximization: The monopolist follows the same universal rule for maximizing profit: it produces the quantity of output where Marginal Revenue equals Marginal Cost ($MR = MC$). After determining this quantity, the firm then looks to the demand curve to find the highest price consumers are willing to pay for that quantity. This price will be significantly greater than the marginal cost of production ($P > MC$).26

- Long-Run Profitability: Because high barriers to entry protect the monopolist from competition, it can sustain supernormal (economic) profits even in the long run. New firms cannot enter the market to compete these profits away.5

The Inefficiency of Monopoly

The monopolist’s market power comes at a significant cost to society in the form of economic inefficiency:

- Productive Inefficiency: A monopolist does not produce at the minimum point of its Average Total Cost (ATC) curve. By restricting output to maximize profit, it typically operates at a quantity where average costs are still falling.33 It fails to produce goods at the lowest possible cost.

- Allocative Inefficiency: This is the primary social cost of monopoly. Because the monopolist sets its price higher than its marginal cost ($P > MC$), the value that consumers place on the last unit produced (the price) is greater than the cost to society of producing it (the marginal cost). This indicates that society would be better off if more units were produced. The monopolist’s decision to restrict output creates a deadweight loss, which represents the total loss of consumer and producer surplus—a measure of lost economic welfare—compared to the perfectly competitive outcome.38

Real-World Examples

While pure monopolies are rare, many firms exhibit monopoly-like characteristics. Public utilities are often government-regulated natural monopolies.4 Historically, giants like Standard Oil and AT&T were broken up by antitrust actions due to their monopolistic control.31 In the modern era, technology behemoths such as Google in the search engine market and Meta in social media face ongoing scrutiny and legal challenges over their dominant market positions and potential abuse of monopoly power.31

Monopolistic Competition: The Crowded Market of Brands

Situated between the theoretical extremes of perfect competition and pure monopoly lies monopolistic competition, a market structure that blends elements of both and is arguably the most common in modern economies.41 It describes a market filled with many firms, each selling a product that is slightly different from its competitors, creating a dynamic of brand-based rivalry.

Defining Characteristics

Monopolistic competition is defined by a unique combination of competitive and monopolistic traits:

- Many Firms: The market contains a large number of independent firms, similar to perfect competition. However, the number is typically smaller, and each firm has a small market share.4

- Differentiated Products: This is the key characteristic that distinguishes it from perfect competition. Firms sell products that are close substitutes but are not identical.44 This differentiation can be based on real differences in quality, design, or features, or on perceived differences created through branding, packaging, advertising, and customer service.41 Everyday examples abound, including restaurants, hair salons, clothing stores, and coffee shops.42

- Low Barriers to Entry and Exit: Like perfect competition, there are few significant obstacles preventing new firms from entering the market when profits are high, or for existing firms to leave when they are unprofitable.41

- Non-Price Competition: Because products are differentiated, firms compete on factors other than just price. Advertising, brand management, and product design are crucial tools used to attract customers and build brand loyalty, giving firms a degree of pricing power.41

Price and Output Determination: Short-Run Power, Long-Run Parity

The product differentiation at the heart of this market structure gives each firm a small degree of monopoly power. As a result, each firm faces its own downward-sloping demand curve, making it a price maker within a limited range.42

- Short-Run Equilibrium: In the short run, a firm in a monopolistically competitive market behaves much like a monopolist. It maximizes its profit by producing the quantity of output where Marginal Revenue equals Marginal Cost ($MR = MC$). It then sets the price according to its demand curve for that quantity. If this price is above the firm’s Average Total Cost (ATC), it will earn supernormal profits.41

- Long-Run Equilibrium: The low barriers to entry are the driving force behind the long-run adjustment. If firms are earning supernormal profits in the short run, this will attract new entrepreneurs to enter the market. As new firms enter, they introduce more substitute products, which causes the demand for each existing firm’s product to decrease (its demand curve shifts to the left). This process continues until all supernormal profits are competed away, and firms are left earning only normal profit (zero economic profit). This long-run equilibrium occurs at the point where the firm’s demand curve is just tangent to its Average Total Cost (ATC) curve.41

Efficiency and the Variety Trade-off

Despite its competitive elements, monopolistic competition does not achieve the ideal efficiency of perfect competition.

- Productive Inefficiency: In the long run, firms in this market structure do not produce at the minimum point of their ATC curve. The tangency point between the downward-sloping demand curve and the ATC curve occurs to the left of the minimum ATC. This means firms operate with excess capacity—they could lower their average costs by increasing production.54

- Allocative Inefficiency: Similar to a monopoly, firms in monopolistic competition set their price higher than their marginal cost ($P > MC$). This creates a deadweight loss, although it is typically smaller than that of a pure monopoly because demand is more elastic.55

- The Benefit of Variety: The primary defense of monopolistic competition is that these inefficiencies are the necessary price society pays for product variety and innovation.54 Consumers benefit from a wide array of choices that cater to different tastes and preferences, a benefit that is absent in the world of homogeneous products under perfect competition.55

A deeper look reveals a subtle contradiction in the model’s assumptions. While the theory posits low barriers to entry, the very mechanism of competition—product differentiation through advertising and branding—can create a significant, practical barrier. A new firm may face low legal or capital hurdles to open, but it must overcome the established brand loyalty of incumbents. This requires substantial and often unrecoverable (sunk) costs in marketing to build brand recognition.58 This financial hurdle, created by the need to advertise, functions as a

de facto barrier to entry, pushing many real-world markets that seem monopolistically competitive closer to the behavior seen in an oligopoly.

Oligopoly: The Arena of Strategic Giants

Oligopoly is a market structure dominated by a few large, powerful firms. This structure is characterized by intense strategic interaction, where the fate of each firm is inextricably linked to the decisions of its rivals.2 Understanding oligopoly requires moving beyond simple profit-maximization rules and into the realm of strategic games.

Defining Characteristics

The defining features of an oligopoly are:

- Few Large Firms: The market is highly concentrated, with a small number of firms controlling the vast majority of the market share.5

- Interdependence: This is the most critical characteristic of an oligopoly. Because there are only a few firms, each must consider the potential reactions of its competitors when making any strategic decision regarding price, output, or advertising.6 One firm’s price cut can trigger a devastating price war, while a new product launch can force rivals to accelerate their own research and development.

- High Barriers to Entry: Similar to a monopoly, significant barriers prevent new competitors from entering the market. These can include enormous economies of scale, patents, high capital requirements for entry, and strong brand loyalty built over years.2

- Homogeneous or Differentiated Products: Oligopolies can exist in markets with standardized products (like steel, aluminum, or oil) or differentiated products (like automobiles, airlines, and smartphones).5

Price and Output Determination: A Complex Strategic Game

Due to the strategic interdependence among firms, there is no single, simple model to explain price and output in an oligopoly. Instead, firm behavior can span a wide range, from aggressive competition to quiet cooperation.

- Collusion and Cartels: Firms may choose to collude to maximize their collective profits. They can form a cartel, which is a formal agreement to restrict output and fix prices, effectively acting as a single monopoly.6 The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is the most famous example of an international cartel.59 While explicit collusion is illegal in many countries, firms may engage in tacit collusion without a formal agreement.

- Price Leadership: A common form of tacit collusion is price leadership, where one firm, often the largest or most efficient, acts as the price leader. When the leader changes its price, the other firms in the industry follow suit. This allows for coordinated pricing without the risk of illegal collusion.60

- Non-Collusive Oligopoly and Price Rigidity: When firms do not collude, they face a great deal of uncertainty. The Kinked Demand Curve model offers one explanation for the price stability often observed in oligopolistic markets. This model assumes that rivals will match any price decrease to avoid losing market share but will ignore any price increase. This creates a “kink” in the firm’s demand curve, making it elastic for price increases and inelastic for price decreases. This kink, in turn, creates a vertical gap in the marginal revenue curve, meaning that a firm’s marginal costs can fluctuate without changing the profit-maximizing price and quantity. This leads to “sticky” or rigid prices.64

Game Theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

The strategic interactions in an oligopoly are often analyzed using game theory, a framework for modeling situations where players’ outcomes depend on the choices of all participants.66 The

Prisoner’s Dilemma is a classic game that perfectly captures the central tension in an oligopoly.

The scenario illustrates why cooperation is so difficult to maintain. Imagine two firms in a duopoly that could both earn high profits by colluding to keep prices high. However, each firm has a powerful individual incentive to cheat on the agreement by lowering its price to capture a larger share of the market. The dilemma is that if both firms act on this incentive to cheat, they both end up with lower prices and lower profits—a worse outcome than if they had cooperated. The Nash Equilibrium of this game is for both firms to defect (cheat), even though mutual cooperation would be collectively superior.68 This inherent instability explains why cartels often break down.

Efficiency

Oligopolies are generally considered inefficient from a societal perspective.

- Allocative and Productive Inefficiency: Like monopolies, oligopolies tend to produce at a quantity where price is greater than marginal cost ($P > MC$), leading to an underproduction of the good from society’s point of view and a deadweight loss.71 They also do not typically produce at the minimum of average total cost, so they are not productively efficient.

- Dynamic Efficiency: A potential positive aspect is that the substantial long-run profits earned by some oligopolies can be a source of funding for significant research and development (R&D). This can lead to innovation, new products, and technological progress, which benefits consumers in the long run. This is often referred to as dynamic efficiency.73

Real-World Examples

Oligopolies are prevalent in many major industries. The global automobile industry, commercial airlines, the U.S. wireless carrier market (dominated by T-Mobile, Verizon, and AT&T), and the recorded music industry are all classic examples of oligopolistic markets.59

A Comparative Overview and Advanced Concepts

Having explored each of the four primary market structures in detail, a direct comparison highlights their fundamental differences. The following table synthesizes the key characteristics, providing an at-a-glance summary of the competitive landscape.

| Characteristic | Perfect Competition | Monopolistic Competition | Oligopoly | Monopoly |

| Number of Firms | Very Many | Many | Few | One |

| Type of Product | Homogeneous/Standardized | Differentiated | Standardized or Differentiated | Unique (No Close Substitutes) |

| Barriers to Entry | None | Low / None | High | Very High / Blocked |

| Control Over Price | None (Price Taker) | Some (Price Maker) | Significant (Interdependent) | Considerable (Price Maker) |

| Demand Curve | Perfectly Elastic (Horizontal) | Downward-Sloping, Elastic | Downward-Sloping, Kinked (in some models) | Downward-Sloping (Market Demand) |

| Profit Maximization | $P = MC$ | $MR = MC$ | Strategic ($MR = MC$ or Collusive) | $MR = MC$ |

| Long-Run Profit | Zero Economic Profit | Zero Economic Profit | Can be Positive | Can be Positive |

| Economic Efficiency | Productively & Allocatively Efficient | Inefficient (Excess Capacity, $P > MC$) | Inefficient ($P > MC$) | Highly Inefficient ($P > MC$) |

| Real-World Examples | Agriculture, Forex | Restaurants, Retail Clothing | Airlines, Automobiles | Public Utilities, Patented Drugs |

Beyond the Big Four: The Theory of Contestable Markets

The traditional models of market structure suggest that market performance (prices, efficiency) is determined by the number of firms and barriers to entry. However, the Theory of Contestable Markets, developed by economist William J. Baumol, offers a crucial refinement. This theory argues that the behavior of firms is driven not just by the actual number of competitors, but by the threat of potential competition.75

A market is considered “contestable” if it has very low barriers to entry and exit, and if there are no significant sunk costs—costs that cannot be recovered upon leaving the market.75 In such a market, potential entrants can engage in

“hit-and-run” competition. If an incumbent firm (even a monopolist) starts earning excessive profits, a new firm can quickly enter the market, undercut the price, capture some of that profit, and then exit just as quickly if the incumbent retaliates by lowering its price, all without losing its initial investment.75

The implication of this theory is profound: the credible threat of such hit-and-run entry can be enough to discipline incumbent firms, forcing them to keep prices close to competitive levels and operate efficiently to deter potential entrants. This suggests that even a market with only one or a few firms can behave competitively if it is highly contestable. This shifts the focus of policy from simply counting the number of firms to analyzing the real conditions of entry and exit in an industry.58

Conclusion: Market Power, Efficiency, and the Role of Regulation

The journey across the spectrum of market structures, from the powerless price takers of perfect competition to the powerful price makers of monopoly, reveals a central theme: the degree of market power held by firms is the primary determinant of prices, output, and economic efficiency. As market power increases, firms gain greater control over price, but this typically comes at the cost of societal welfare.

The benchmark of perfect competition establishes the conditions for perfect efficiency, where resources are allocated to maximize societal well-being. As we move away from this ideal into the real-world domains of monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly, we see a consistent pattern: increasing market power leads to higher prices, lower output, and a loss of both productive and allocative efficiency. This inefficiency represents a form of market failure, where the market, left to its own devices, fails to produce the optimal outcome for society.

It is precisely because of these market failures that governments play a crucial role in the economy. Recognizing that monopolies and collusive oligopolies can harm consumers through anti-competitive practices, most market-based economies have enacted antitrust laws. In the United States, landmark legislation like the Sherman Act, which outlaws monopolization and price-fixing conspiracies, and the Clayton Act, which prohibits mergers and acquisitions that substantially lessen competition, form the bedrock of competition policy.79 These regulations are designed to prevent the abuse of market power, promote competition, and ultimately protect the interests of consumers, ensuring that the benefits of the market system are broadly shared.

Works cited

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed September 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Market_structure#:~:text=Market%20structure%2C%20in%20economics%2C%20depicts,by%20external%20factors%20and%20elements.

- Market structure – Wikipedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Market_structure

- Market Structure – University of West Georgia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.westga.edu/~bquest/1997/ecnmkt.html

- A Guide to Types of Market Structures – Aurora University Online Degree Programs, accessed September 14, 2025, https://online.aurora.edu/types-of-market-structures/

- Market structures | Research Starters – EBSCO, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/economics/market-structures

- Market Structure – Overview, Definition, Features, and Types – Corporate Finance Institute, accessed September 14, 2025, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/market-structure/

- Monopolistic Market vs. Perfect Competition: What’s the Difference? – Investopedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/040915/what-difference-between-monopolistic-market-and-perfect-competition.asp

- What Are the Main Features of Perfect Competition? – Amrita Online, accessed September 14, 2025, https://onlineamrita.com/blog/what-are-the-main-features-of-perfect-competition/

- These four characteristics mean that a given perfectly competitive firm is unable to exert any control whatsoever over the market. The large number of small firms, all producing identical products, means that a large (very, very large) number of perfect substitutes exists for the output produced by any given firm. – AmosWEB is Economics: Encyclonomic WEB*pedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.amosweb.com/cgi-bin/awb_nav.pl?s=wpd&c=dsp&k=perfect+competition,+characteristics

- Characteristics of Perfect Competition | PDF – Scribd, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/402188007/Perfect-Competition-docx

- Perfect Competition – Economics: Edexcel A A Level – Seneca, accessed September 14, 2025, https://senecalearning.com/en-GB/revision-notes/a-level/economics/edexcel/a/6-1-2-perfect-competition

- Perfect competition and why it matters (article) | Khan Academy, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.khanacademy.org/economics-finance-domain/microeconomics/perfect-competition-topic/perfect-competition/a/perfect-competition-and-why-it-matters-cnx

- Perfect Competition: The Theory and Why It Matters – Outlier Articles, accessed September 14, 2025, https://articles.outlier.org/perfect-competition

- Perfect Competition – Definition, Example, Price-Takers – Corporate Finance Institute, accessed September 14, 2025, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/perfect-competition/

- Perfect Competition – William Branch, accessed September 14, 2025, http://www.williambranch.org/perfect-competition

- Diagram of Perfect Competition – Economics Help, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/198/economics/diagrams-of-perfect-competition/

- www.vedantu.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.vedantu.com/commerce/price-determination-under-perfect-competition#:~:text=Since%20a%20firm%20in%20perfect,its%20Marginal%20Revenue%20(MR).

- Price-and-Output-Determination-Under-Perfect-Competition-Market – Tilak Singh Mahara, accessed September 14, 2025, https://tilakmahara.com.np/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/price-and-output-determination-under-perfect-competition-market.pdf

- Perfect Competition – AP Micro Study Guide – Fiveable, accessed September 14, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/ap-micro/unit-3/perfect-competition/study-guide/T08vY2meNhtpbLCT83uH

- Market Structure Diagrams – The Curious Economist, accessed September 14, 2025, https://thecuriouseconomist.com/market-structure-diagrams/

- Perfect Competition and Efficiency: Videos & Practice Problems – Pearson, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.pearson.com/channels/microeconomics/learn/brian/ch-11-perfect-competition/perfect-competition-and-efficiency

- www.pearson.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.pearson.com/channels//microeconomics/learn/brian/ch-11-perfect-competition/perfect-competition-and-efficiency#:~:text=Productive%20efficiency%20in%20a%20perfectly%20competitive%20market%20occurs%20when%20firms,ATC)%20at%20its%20minimum%20point.

- Efficiency in perfectly competitive markets (article) – Khan Academy, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.khanacademy.org/economics-finance-domain/microeconomics/perfect-competition-topic/perfect-competition/a/efficiency-in-perfectly-competitive-markets-cnx

- Perfect Competition | Definition, Benefits & Examples – Lesson, accessed September 14, 2025, https://study.com/learn/lesson/perfect-competition-characterisitcs-market-examples.html

- Perfect Competition: 3 Examples of the Economic Theory – 2025 – MasterClass, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.masterclass.com/articles/perfect-competition-examples

- Monopoly – Wikipedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monopoly

- What Is a Monopoly? Types, Regulations, and Impact on Markets, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/monopoly.asp

- Monopoly Characteristics Flashcards – Quizlet, accessed September 14, 2025, https://quizlet.com/103063291/monopoly-characteristics-flash-cards/

- Monopoly Power in Markets | Reference Library | Economics – Tutor2u, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.tutor2u.net/economics/reference/monopoly-revision-presentation

- Monopoly in Economics | Definition, Characteristics & Types – Lesson – Study.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-a-monopoly-in-economics-definition-impact-on-consumers.html

- Examples of Monopoly – Fundsnet Services, accessed September 14, 2025, https://fundsnetservices.com/examples-of-monopoly

- Price & Output Determination in Monopoly & Imperfect Markets, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.jandkicai.org/pdf/16786Markets_Part_2.pdf

- Price Determination Under Monopoly – Perfect Competition – Scribd, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/370520677/Price-Determination-Under-Monopoly

- UNIT 10 MONOPOLY: PRICE AND OUTPUT DECISIONS – eGyanKosh, accessed September 14, 2025, https://egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/67487/1/Unit-10.pdf

- 9.2 How a Profit-Maximizing Monopoly Chooses Output and Price – Principles of Economics 3e | OpenStax, accessed September 14, 2025, https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/9-2-how-a-profit-maximizing-monopoly-chooses-output-and-price

- 9.3 Single Monopoly Price and Output – Principles of Microeconomics – eCampusOntario Pressbooks, accessed September 14, 2025, https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/principlesofmicroeconomicscdn/chapter/9-3-single-monopoly-price-and-output/

- Output and Price Determination in Pure monopoly | Finance & Economics!!!, accessed September 14, 2025, https://justdan93.wordpress.com/2012/07/21/output-and-price-determination-in-pure-monopoly/

- Monopoly & Efficiency – Economics Tuition SG, accessed September 14, 2025, https://economics-tuition.sg/monopoly-efficiency/

- courses.lumenlearning.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-microeconomics/chapter/the-inefficiency-of-monopoly/#:~:text=Thus%2C%20monopolies%20don’t%20produce,in%20a%20perfectly%20competitive%20market.

- www2.harpercollege.edu, accessed September 14, 2025, http://www2.harpercollege.edu/mhealy/eco211f/lectures/monopoly/monopoly.htm#:~:text=Examples%20%2F%20Importance-,1.,examples%20of%20%22near%22%20monopolies.

- 3.4.3 Monopolistic Competition (Edexcel) | Reference Library | Economics – Tutor2u, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.tutor2u.net/economics/reference/3-4-3-monopolistic-competition-edexcel

- Monopolistic Competition – definition, diagram and examples – Economics Help, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/311/markets/monopolistic-competition/

- Monopolistic Competition: Definition, How it Works, Pros and Cons, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/monopolisticmarket.asp

- Monopolistic competition – Wikipedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monopolistic_competition

- Note on Monopolistic Competition, accessed September 14, 2025, https://msbrijuniversity.ac.in/assets/uploads/newsupdate/Monopolistic.pdf

- Characteristics of monopolistic competition | Intermediate Microeconomic Theory Class Notes | Fiveable, accessed September 14, 2025, https://fiveable.me/intermediate-microeconomic-theory/unit-5/characteristics-monopolistic-competition/study-guide/v5oQQMejfPmvIeRI

- Monopolistic Competition – Meegle, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.meegle.com/en_us/topics/economic/monopolistic-competition

- www.wallstreetprep.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/monopolistic-competition/#:~:text=Commonly%20cited%20examples%20of%20industries,and%20Footwear%2C%20e.g.%20Shoe%20Stores

- What are the characteristics of monopolistic competition? – buildd, accessed September 14, 2025, https://buildd.co/marketing/what-are-the-characteristics-of-monopolistic-competition

- 10.1 Monopolistic Competition – Principles of Microeconomics – Hawaii Edition, accessed September 14, 2025, https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/principlesofmicroeconomics/chapter/10-1-monopolistic-competition/

- www.scribd.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/presentation/25969174/Price-and-Output-Determination-Under-Monopolistic-Competiton#:~:text=entry%20and%20exit.-,2)%20Under%20monopolistic%20competition%2C%20a%20firm%20determines%20price%20and%20output,the%20price%20and%20average%20cost.

- Price-and-Output-Determination-Under-Monopolistic-Competition – Tilak Singh Mahara, accessed September 14, 2025, https://tilakmahara.com.np/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Price-and-Output-Determination-Under-Monopolistic-Competition.pdf

- Section 2: Short-Run and Long-Run Profit Maximization for a Firm in Monopolistic Competition | Inflate Your Mind, accessed September 14, 2025, https://inflateyourmind.com/microeconomics/unit-8-microeconomics/section-2-short-run-and-long-run-profit-maximization-for-a-firm-in-monopolistic-competition/

- Reading: Monopolistic Competition and Efficiency | Microeconomics – Lumen Learning, accessed September 14, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-microeconomics/chapter/monopolistic-competition-and-efficiency/

- Efficiency in Monopolistic Competition: Videos & Practice Problems – Pearson, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.pearson.com/channels/microeconomics/learn/brian/ch-13-monopolistic-competition/efficiency-in-monopolistic-competition

- Monopolistic Competition and Efficiency | Microeconomics – Lumen Learning, accessed September 14, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-microeconomics/chapter/monopolistic-competition-and-efficiency/

- Reading: Monopolistic Competition and Efficiency – Microeconomics, accessed September 14, 2025, https://library.achievingthedream.org/sacmicroeconomics/chapter/monopolistic-competition-and-efficiency/

- Contestable markets – Economics Help, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.economicshelp.org/microessays/contestable-markets/

- Oligopoly: Meaning and Characteristics in a Market – Investopedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/oligopoly.asp

- Price and Output Determination under Oligopoly, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/oligopoly/price-and-output-determination-under-oligopoly/7352

- Price and Output Determination Under Oligopoly – Explanation and FAQs – Vedantu, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.vedantu.com/commerce/price-and-output-determination-under-oligopoly

- The Most Notable Oligopolies in the US – Investopedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/010915/what-are-most-famous-cases-oligopolies.asp

- 13.2: Oligopoly in Practice – Social Sci LibreTexts, accessed September 14, 2025, https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Economics/Introductory_Comprehensive_Economics/Economics_(Boundless)/13%3A_Oligopoly/13.02%3A_Oligopoly_in_Practice

- Price determination under oligopoly | PPTX – SlideShare, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/price-determination-under-oligopoly/52617328

- Price-output determination under oligopoly, Managerial Economics – Expertsmind.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.expertsmind.com/questions/price-output-determination-under-oligopoly-30197365.aspx

- Prisoner’s dilemma | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/social-sciences-and-humanities/prisoners-dilemma

- Prisoner’s Dilemma | Microeconomics – Lumen Learning, accessed September 14, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-microeconomics/chapter/prisoners-dilemma/

- 11.4 The Oligopoly Version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma – Principles of Microeconomics – eCampusOntario Pressbooks, accessed September 14, 2025, https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/principlesofmicroeconomicscdn/chapter/11-4-the-oligopoly-version-of-the-prisoners-dilemma/

- What Is the Prisoner’s Dilemma and How Does It Work? – Investopedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/prisoners-dilemma.asp

- 5.3 Oligopoly (continued) – New Prairie Press, accessed September 14, 2025, https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&filename=29&article=1012&context=ebooks&type=additional

- Outcome: Inefficiency in Oligopolies | Microeconomics – Lumen Learning, accessed September 14, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-microeconomics/chapter/learning-outcome-3/

- Price Determination under Oligopoly – OoCities.org, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.oocities.org/znuniverse/micro_economics/Price_Determination_under_Oligopoly.htm

- 3.4.1 Efficiency (Edexcel) | Reference Library | Economics – Tutor2u, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.tutor2u.net/economics/reference/3-4-1-efficiency-edexcel

- www.investopedia.com, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-are-some-current-examples-oligopolies.asp#:~:text=Some%20of%20the%20most%20notable,have%20resulted%20in%20industry%20consolidation.

- Contestable Market Theory: Definition, How It Works, and Methods, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/contestablemarket.asp

- Contestable market – Wikipedia, accessed September 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contestable_market

- Contestable Markets — Mr Banks Economics Hub | Resources, Tutoring & Exam Prep, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.mrbanks.co.uk/contestable-markets

- Deregulation and the Theory of Contestable Markets – CORE, accessed September 14, 2025, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/72838009.pdf

- The Antitrust Laws | Federal Trade Commission, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/advice-guidance/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/antitrust-laws

Leave a Reply