Introduction: Why Economic Theories Matter

From the stimulus checks that arrived during the COVID-19 pandemic to the news reports on the Federal Reserve’s battle against inflation, the abstract world of economic theory has a profound and tangible impact on our daily lives. These policies are not born in a vacuum; they are the practical application of powerful ideas, the culmination of centuries of debate about how economies work and the proper role of government within them.1 At its heart, the history of economic policy is a grand tug-of-war between two fundamental beliefs: a deep faith in the market’s ability to regulate itself and a conviction that the state must intervene to correct its inherent flaws.

This report embarks on an intellectual journey through the major schools of economic thought. We will begin with the Classical school’s foundational belief in a self-correcting market, explore the revolutionary challenge posed by Keynesianism in the face of the Great Depression, and examine the Monetarist counter-revolution that rose from the ashes of 1970s stagflation. Finally, we will navigate the complex landscape of modern theories, from Supply-Side economics to the radical propositions of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), to understand the ideas shaping our world today.

Section 1: The Classical Foundation: The Unseen Hand of the Market (c. 1776 – 1930s)

The Birth of Modern Economics

Emerging from the intellectual dynamism of the Enlightenment and the transformative chaos of the Industrial Revolution, Classical economics was the first systematic attempt to understand the new capitalist world.3 Thinkers like Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill sought to explain the forces of economic growth, moving beyond the mercantilist obsession with hoarding gold to focus on production, labor, and trade.4

Core Tenets: A Self-Regulating System

The central pillar of Classical thought is the belief that free markets are inherently self-regulating and naturally gravitate toward full employment.7 This confidence was built on the assumption that wages and prices are flexible, adjusting automatically to balance supply and demand across all markets.8 In this worldview, government intervention is not only unnecessary but often harmful, as it can distort the market’s efficient, natural equilibrium.8 This philosophy is encapsulated in the doctrine of

laissez-faire, a French term meaning “let them do,” which advocates for minimal government interference in the economy.10

Conceptual Pillars of the Classical School

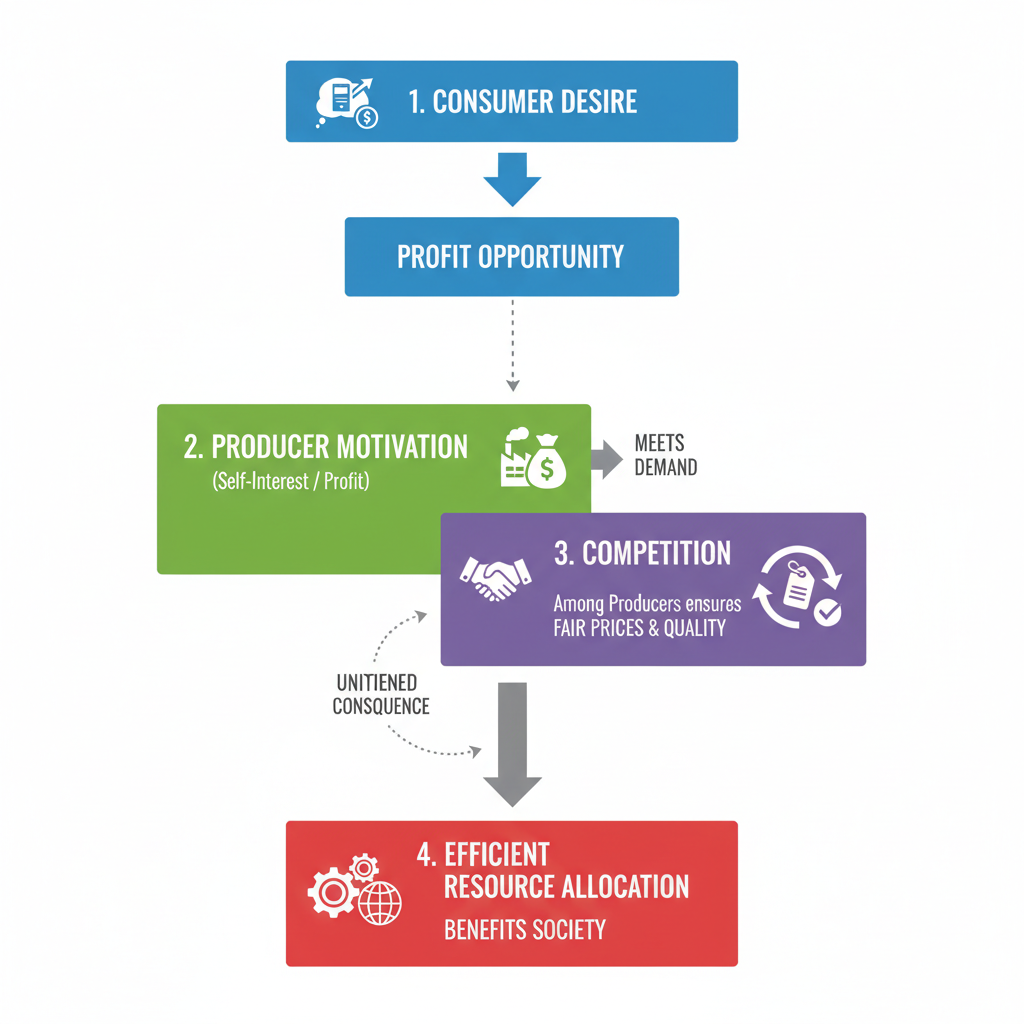

Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand”

Perhaps the most enduring metaphor in all of economics is Adam Smith’s “invisible hand.” In the popular understanding, it describes how individuals pursuing their own self-interest—the baker baking bread to earn a living, not out of benevolence—are unintentionally guided, as if by an unseen force, to promote the greater good of society.12 The price mechanism is the engine of this process, signaling where resources are needed and coordinating the actions of millions without any central direction.12

However, the modern, sweeping interpretation of the invisible hand as a universal law that guarantees optimal social outcomes is a significant expansion of Smith’s original, more modest point. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith mentions the concept only once, in a specific discussion about international trade.14 He argued that a merchant, fearing the risks of sending his capital abroad, would prefer to invest domestically. In doing so, he “intends only his own security” but is “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention”—namely, the prosperity of his home country.14 This was not a blanket endorsement of deregulation but a specific observation about capital investment. Twentieth-century economists popularized the term as a broad justification for laissez-faire policy, a usage that goes far beyond Smith’s own nuanced view, which acknowledged that the interests of businessmen could often run contrary to the public good.14

Say’s Law of Markets

Another cornerstone of Classical thought is Say’s Law, often summarized as “supply creates its own demand”.7 The French economist Jean-Baptiste Say argued that the act of producing goods and services generates the income (in the form of wages, profits, and rent) necessary to purchase them.17 In this framework, money is just a medium of exchange; people ultimately trade their production for the production of others.16 The critical implication of this law is that a “general glut”—a prolonged, economy-wide surplus of goods caused by insufficient demand—is impossible.16 While there could be temporary overproduction of a specific good, the overall system would always find its balance. This belief provided the theoretical foundation for the Classical school’s confidence that the economy would always self-correct.

Classical Economics in Practice: The Myth of Pure Laissez-Faire

The 19th century in Britain and the “Gilded Age” in the United States are often held up as the golden era of laissez-faire capitalism.19 Yet, a closer look reveals a more complex reality. The historical record shows that the state was not absent but was, in fact, instrumental in creating the conditions for the market to function. Governments actively established and enforced the institutional framework of capitalism, including property rights, contract law, and patent systems, which lowered transaction costs and facilitated trade.21 Furthermore, governments continued to use tariffs and other interventions to support strategic industries.22

The decline in the popularity of pure laissez-faire philosophy toward the end of the 19th century was a direct response to the real-world consequences of rapid, unregulated industrialization: vast economic inequality, dangerous working conditions, and the rise of powerful monopolies.19 The “unseen hand” did not automatically solve these acute social problems, demonstrating that the ideal of a purely self-regulating market has always been more of a theoretical construct than a practical reality. The true debate has never been about intervention versus no intervention, but about the appropriate form and extent of government action.

Section 2: The Keynesian Revolution: The Visible Hand of Government (c. 1936 – 1970s)

The Great Depression: A Crisis of Theory

The Great Depression of the 1930s was more than an economic catastrophe; it was an intellectual crisis that shattered the foundations of Classical economics.24 For over a decade, mass unemployment persisted, defying the Classical belief in self-correcting markets and full employment.25 This failure created an opening for British economist John Maynard Keynes, whose 1936 masterpiece,

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, proposed a revolutionary new framework for understanding and managing capitalist economies.6

The Keynesian Critique

Keynes inverted the logic of the Classical school. He argued that the primary driver of economic activity and employment is not supply, but aggregate demand—the total spending by households, businesses, and the government.26 If aggregate demand is insufficient, an economy can become trapped in a vicious cycle of low output and high unemployment for a prolonged period.26 In Keynes’s view, it is demand that creates its own supply, not the other way around.17

He also challenged the Classical assumption of flexible wages. Keynes observed that in the real world, wages are “sticky downwards”.9 Due to labor contracts and social norms, workers strongly resist cuts to their nominal pay, even during a downturn.28 This wage rigidity prevents the labor market from “clearing” (i.e., reaching an equilibrium where everyone who wants a job can find one), leading to persistent involuntary unemployment.9

The Keynesian Policy Toolkit

The Keynesian diagnosis led to a radical new prescription: the government must actively manage aggregate demand to stabilize the economy.

Counter-Cyclical Fiscal Policy

During a recession, when private consumption and investment collapse, the government must step in as the “spender of last resort”.26 It should implement

expansionary fiscal policy—increasing government spending on projects like infrastructure or cutting taxes to leave more money in consumers’ pockets—to boost aggregate demand, even if it requires running a budget deficit.1 Conversely, during an economic boom when inflation is a threat, the government should implement contractionary fiscal policy—cutting spending or raising taxes—to cool the economy down.26 This approach, acting against the grain of the business cycle, positions the government as a balance wheel for the economy.24

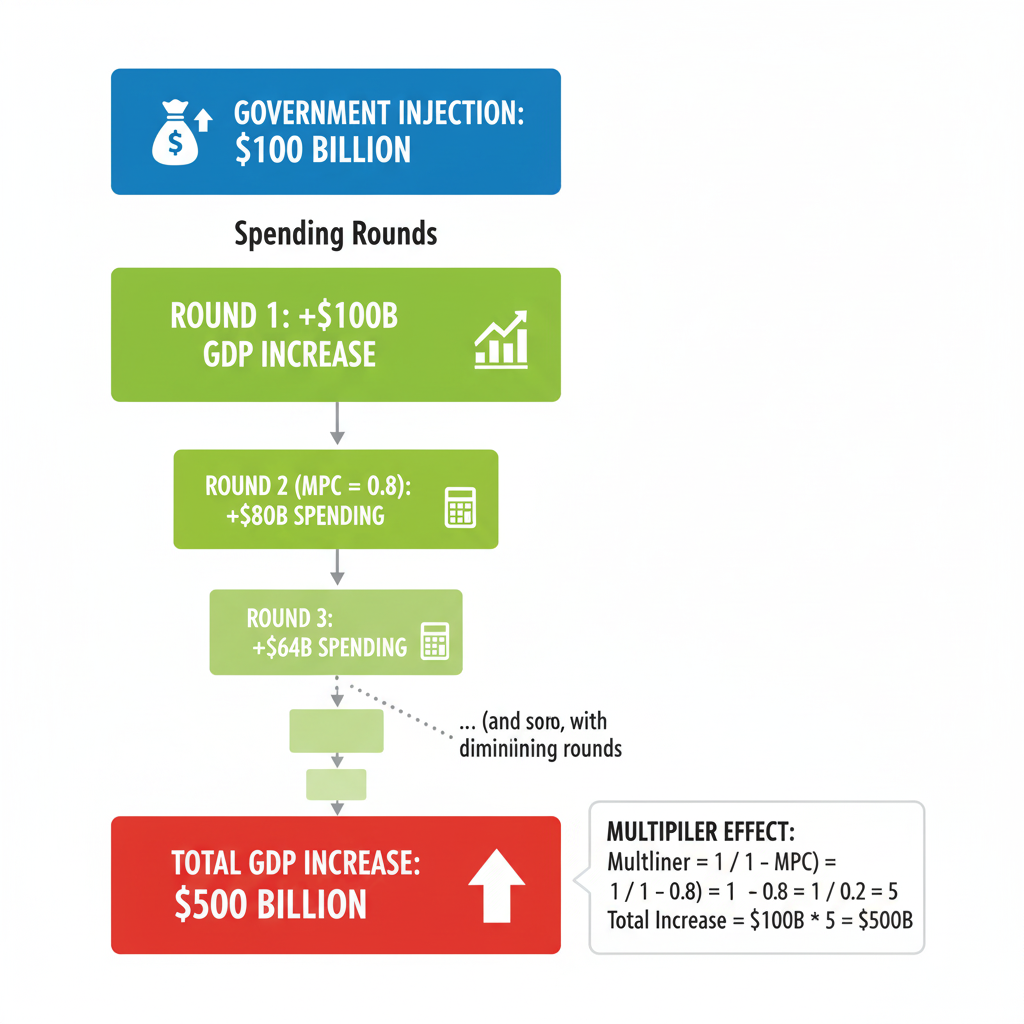

The Multiplier Effect

Central to the Keynesian argument is the multiplier effect. This concept holds that an initial change in spending has a magnified final impact on the national income.26 When the government spends money on a new bridge, for example, that money becomes income for engineers and construction workers. They, in turn, spend a portion of this new income (a proportion known as the Marginal Propensity to Consume, or MPC), which then becomes income for grocers, landlords, and car dealers. This chain reaction of spending ripples through the economy, leading to a total increase in GDP that is a multiple of the original injection.31

However, the power of this multiplier is not a fixed constant. Its real-world effectiveness depends heavily on “leakages” from the circular flow of income.31 The simple formula, 1/(1−MPC), becomes more complex in an open economy with a government, where the denominator is the sum of the Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS), the Marginal Propensity to Tax (MPT), and the Marginal Propensity to Import (MPM).32 If fearful consumers choose to save their stimulus checks (high MPS), or if the money is spent on imported goods (high MPM), the domestic multiplier effect is dampened. This complexity explains why economists often disagree on the precise size of the multiplier and why the impact of fiscal stimulus can vary significantly depending on the economic context.

Keynesianism in Practice

The U.S. New Deal under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with its massive public works programs like the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), is often seen as a real-world application of Keynesian principles before the theory was even fully formalized.34 These programs used large-scale government spending to create jobs and stimulate economic activity, fundamentally altering the role of the federal government in the American economy.35

The true heyday of Keynesianism, however, was the post-World War II “Golden Age of Capitalism”.9 From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, Western governments widely adopted Keynesian demand-management policies.37 This period was characterized by unprecedented economic stability, high growth, and low unemployment.38

The success of Keynesianism in solving the problem of mass unemployment highlights a crucial lesson about economic thought: its dominance is often cyclical and context-dependent. Keynesian theory provided the perfect tools for the challenges of its time but was ultimately ill-equipped to handle the novel problem that emerged in the 1970s: stagflation, the toxic combination of stagnant economic growth and high inflation.26 The Keynesian framework, which was built on an assumed trade-off between inflation and unemployment (known as the Phillips Curve), had no clear policy response for a situation where both were rising simultaneously.27 This failure created an intellectual vacuum, paving the way for the rise of a new school of thought.

Section 3: The Monetarist Counter-Revolution: In Money We Trust (c. 1970s – 1980s)

The Great Stagflation and the Rise of Friedman

The economic turmoil of the 1970s, marked by soaring inflation and sluggish growth, left Keynesian policymakers baffled.37 Into this void stepped Milton Friedman, a Nobel laureate from the University of Chicago, who offered a compelling alternative: Monetarism.39 Friedman argued that the Keynesian focus on discretionary fiscal policy was misguided and often a source of instability.41 He contended that inflation was not caused by strong demand or union power, but simply by an excessive growth in the money supply.42 In a famous re-interpretation of history, Friedman and his co-author Anna Schwartz argued that the Great Depression itself was not a failure of free-market capitalism, but a catastrophic failure of government policy—specifically, the Federal Reserve’s failure to prevent the money supply from collapsing.41

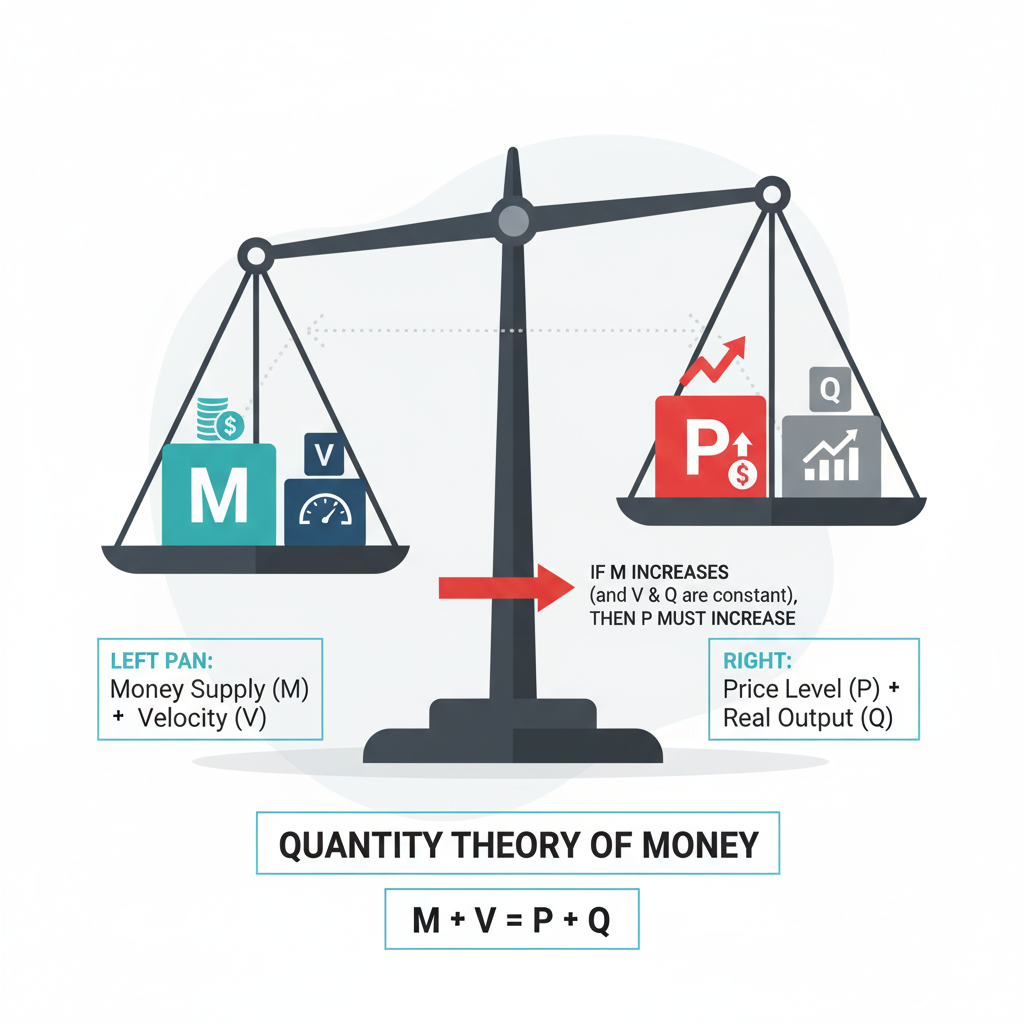

The Foundation: The Quantity Theory of Money

The intellectual core of Monetarism is a revival of the old Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), summarized by the equation of exchange: MV=PQ.43

- M = The total Money Supply in the economy.

- V = The Velocity of Money, or the average number of times a dollar is spent in a year.

- P = The overall Price Level.

- Q = The economy’s Real Output of goods and services (Real GDP).

The equation itself is an accounting identity, meaning it is true by definition.43 The Monetarist revolution was to turn it into a powerful theory by making a crucial assumption: that the velocity of money (

V) is relatively stable and predictable.27 Because they also believed that real output (Q) is determined by supply-side factors (like technology and resources) in the long run, a direct, causal relationship emerges: changes in the money supply (M) lead directly to changes in the price level (P).44 This is the basis for Friedman’s famous assertion that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.38

Monetarist Policy Prescriptions

Based on this framework, Monetarists advocated for a radical shift in economic policy.

- Rules over Discretion: Deeply skeptical of the ability of policymakers to fine-tune the economy, Friedman argued against discretionary intervention.41 He proposed a

constant money growth rule: the central bank should abandon its attempts to manage interest rates or unemployment and instead be bound to a simple rule of increasing the money supply by a slow, steady rate (e.g., 2-3% per year) to accommodate real economic growth without fueling inflation.41 - The Natural Rate of Unemployment: Monetarism also introduced the concept of a “natural rate of unemployment,” determined by the structural features of the labor market (like skills mismatches or welfare policies).45 Any attempt by the government to use stimulus to push unemployment below this natural rate would be futile in the long run and would only lead to accelerating inflation.46

Monetarism in Practice

The most significant real-world test of Monetarist policy occurred in the early 1980s. Facing double-digit inflation, U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker implemented a staunchly Monetarist strategy, severely tightening the money supply.41 The policy was a brutal success: inflation was brought under control, but at the cost of a deep recession and high unemployment.42

Despite this apparent victory, Monetarism’s reign as a practical policy guide was short-lived. Its Achilles’ heel proved to be its core assumption: the stability of the velocity of money. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, financial innovation (like ATMs and credit cards) and changing banking regulations caused velocity to become highly erratic and unpredictable.41 The stable link between the money supply and inflation broke down. When central banks tried to target a specific measure of the money supply, they found that velocity would shift unexpectedly, making the policy ineffective.44 This empirical failure is why virtually all major central banks today, including the Fed, target short-term interest rates instead of the money supply, marking a quiet end to the Monetarist experiment.

Section 4: Modern Challengers and the New Synthesis

The modern economic landscape is not defined by a single dominant ideology but by a dynamic interplay of competing theories and a mainstream synthesis that borrows from past schools.

Supply-Side Economics

Rising to prominence in the 1980s under the banner of “Reaganomics,” Supply-Side economics argues that economic growth is most effectively stimulated by lowering barriers to production.48 In direct opposition to the Keynesian focus on demand, supply-siders contend that producers and their willingness to create goods and services are the true engine of prosperity.48 Their primary policy tools are tax cuts—particularly for corporations and investors—and deregulation, which are intended to provide powerful incentives to work, save, and invest.49 The theoretical foundation for this is the

Laffer Curve, which posits that if tax rates are prohibitively high, a reduction in those rates can actually increase government revenue by spurring a massive expansion of the underlying economic activity (the tax base).48

The Austrian School

The Austrian School, with key figures like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, represents a more radical free-market position. While its policy conclusions—sound money, minimal government, opposition to central banking—are well-known, its most fundamental distinction lies in its methodology.50 Austrians largely reject the mathematical and statistical methods (econometrics) that dominate mainstream economics.51 They argue that human action is too complex, subjective, and unpredictable to be captured by quantitative models. Instead, they rely on a method of verbal logic called “praxeology” to deduce economic laws from the basic axioms of human choice.51 This methodological divide is not just a disagreement over policy but a profound challenge to how economic knowledge itself should be derived. Key Austrian concepts include the theory of the business cycle, which blames central bank credit expansion for creating artificial booms that inevitably lead to busts, and the idea of the market as a “spontaneous order” that emerges from human action but not human design.51

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

The most recent and perhaps most controversial challenger to mainstream thought is Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). MMT fundamentally inverts the conventional understanding of government finance for a country that issues its own currency, like the United States.52 The traditional view, shared by nearly all other schools, is that a government must tax or borrow to finance its spending. MMT argues the opposite is true: a sovereign government’s spending creates new money ex nihilo.53

In this framework, taxes do not fund spending; their primary purposes are to create a demand for the government’s currency and to withdraw money from the economy to control inflation.52 The central claim of MMT is that such a government can never be forced to default on debt denominated in its own currency because it can always create the money to make the payments.52 Therefore, the true constraint on government spending is not a lack of revenue, but the availability of real resources (labor, materials, factories) and the risk of causing inflation if spending outstrips the economy’s productive capacity.53 This paradigm shift challenges the very basis of mainstream debates about deficits and debt.

The New Neoclassical Synthesis

Today, mainstream macroeconomics is best described as a “New Neoclassical Synthesis.” It blends insights from different schools, using a largely Keynesian framework to understand short-run economic fluctuations (acknowledging sticky wages and the importance of aggregate demand) while adopting Classical and Monetarist ideas for the long run (recognizing the importance of supply-side factors and the principle that money is neutral in the long term).6

Section 5: The Enduring Debate: A Comparative Framework and Conclusion

The history of economic thought is not a linear march toward a single truth, but a cyclical debate where old ideas are constantly re-evaluated in light of new challenges. The 2008 global financial crisis, a massive failure of aggregate demand, prompted a “Keynesian moment” with large-scale government stimulus packages.26 In contrast, the surge in inflation following the COVID-19 pandemic revived Monetarist arguments about the dangers of excessive money creation and Supply-Side concerns about production bottlenecks.

To synthesize this complex history, the following table provides a comparative overview of the major schools of thought.

Table 1: The Schools of Economic Thought at a Glance

| School of Thought | Core Belief | Primary Problem to Solve | Preferred Policy Tool | View on Government Intervention |

| Classical | Markets are self-regulating and tend toward full employment. 7 | Inefficiency caused by government interference. 8 | Laissez-faire; free trade. 7 | Minimal; limited to enforcing contracts and property rights. 8 |

| Keynesian | Aggregate demand drives the economy; markets can fail and get stuck. 26 | Demand-deficient unemployment. 9 | Counter-cyclical fiscal policy (spending/taxes). 2 | Active and discretionary intervention to manage the business cycle. 1 |

| Monetarist | The money supply is the primary determinant of nominal GDP and inflation. 41 | Inflation caused by excessive money growth. 39 | Rules-based monetary policy (controlling the money supply). 41 | Limited and rules-based; skeptical of discretionary fiscal policy. 27 |

| Supply-Side | Production (supply) and incentives are the key to growth. 49 | Stagnant growth caused by high taxes and regulation. 48 | Tax cuts and deregulation. 49 | Reduce the size and scope of government to unleash production. 49 |

| Austrian | The economy is a complex, spontaneous order driven by individual action. 51 | Distortions and business cycles caused by central bank credit manipulation. 51 | Free banking; sound money (e.g., gold standard). 51 | Radically minimal; opposes central banking and most regulation. 51 |

| MMT | A sovereign currency issuer is not financially constrained by revenue. 52 | Unemployment (evidence of insufficient government spending). 53 | Fiscal policy to ensure full employment, with taxes to control inflation. 53 | The government is responsible for using its currency-issuing power to maintain full employment. 53 |

Ultimately, no single school holds a monopoly on economic wisdom. The enduring debate between these competing visions is not a sign of failure but of a vibrant and essential intellectual process. The most effective economic policies often involve a pragmatic synthesis, drawing on different insights to address the unique challenges of the time. The goal of understanding these theories is not to declare a winner, but to build a more versatile and nuanced toolkit for navigating our complex economic world.

Works cited

- Aggregate Demand | Research Starters – EBSCO, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/business-and-management/aggregate-demand

- How Do Fiscal and Monetary Policies Affect Aggregate Demand? – Investopedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/040315/how-do-fiscal-and-monetary-policies-affect-aggregate-demand.asp

- Classical Economics: Unveiling the Market Mechanisms and Legacy for Economic Thinking, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/classical-economics-unveiling-the-market-mechanisms-and-legacy-for-economic-thinking-100222.html

- Understanding Classical Growth Theory: Key Concepts and …, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/classical-growth-theory.asp

- www.libertarianism.org, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.libertarianism.org/topics/classical-economics#:~:text=Classical%20economics%20refers%20to%20a,Ricardo%2C%20and%20John%20Stuart%20Mill.

- Classical Economics: A Libertarianism.org Guide, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.libertarianism.org/topics/classical-economics

- www.pw.live, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.pw.live/commerce/exams/classical-economics#:~:text=What%20are%20the%20main%20principles,to%20equilibrium%20without%20government%20intervention.

- Classical Economics – (Principles of Economics) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed October 5, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/principles-econ/classical-economics

- Classical vs. Keynesian Perspectives | Intermediate Macroeconomic …, accessed October 5, 2025, https://fiveable.me/intermediate-macroeconomic-theory/unit-12/classical-vs-keynesian-perspectives/study-guide/frDfzLSh9FqLbklP

- www.law.cornell.edu, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/laissez-faire#:~:text=Laissez%2Dfaire%20refers%20to%20an,of%20a%20free%20market%20economy.

- laissez-faire | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/laissez-faire

- What is the Invisible Hand of the market? | Reference Library | Economics – Tutor2u, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.tutor2u.net/economics/reference/what-is-the-invisible-hand-of-the-market

- Understanding the Invisible Hand in Economics: Key Insights – Investopedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/invisiblehand.asp

- Invisible hand – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invisible_hand

- The Invisible Hand Symbol in The Wealth of Nations | LitCharts, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.litcharts.com/lit/the-wealth-of-nations/symbols/the-invisible-hand

- Say’s law – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Say%27s_law

- Say’s Law of Market Say’s law of markets is the core of the classical theory of employment. An early 19th century French Econo – Gyan Sanchay, accessed October 5, 2025, https://gyansanchay.csjmu.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Says-Law-of-Market.pdf

- Chapter 8, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.ux1.eiu.edu/~mqdao/Chapter%2009_Arnold.pptx

- Laissez-faire | Definition, Economics, Government, Policy, History, & Facts – Britannica, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/money/laissez-faire

- Laissez-faire policies in the Gilded Age (article) | Khan Academy, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-us-history/period-6/apush-controversies-over-the-role-of-government-in-the-gilded-age-lesson/a/laissez-faire-policies-in-the-gilded-age

- Government and the economy, 1688–1850 – Center for the Economics of Human Development, accessed October 5, 2025, https://jenni.uchicago.edu/WJP/papers/Harris_govt_and_econ.pdf

- Laissez Faire and the Industrial Revolution (Chapter 3) – Monitoring …, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/monitoring-the-state-or-the-market/laissez-faire-and-the-industrial-revolution/15DFF2A0AA63662B4FA6A450FA6C2783

- BRIA 19 2 b Social Darwinism and American Laissez-faire Capitalism – Online Lessons – Bill of Rights in Action – Teach Democracy, accessed October 5, 2025, https://teachdemocracy.org/online-lessons/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-19-2-b

- Keynesian Economics and the Great Depression: A Tale of Intervention and Recovery, accessed October 5, 2025, https://econ.sites.northeastern.edu/wiki/4785-2/aggregate-expenditures/keynesian-economics-and-the-great-depression-a-tale-of-intervention-and-recovery/

- New Classical Macroeconomics – Econlib, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/NewClassicalMacroeconomics.html

- What Is Keynesian Economics? – Back to Basics – Finance & Development, September 2014, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/09/basics.htm

- Keynesian Economics vs Monetarist Economics: Definitions …, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.vedantu.com/commerce/difference-between-keynesian-economics-and-monetarist-economics

- Post World War II politics and Keynes’s aborted revolutionary economic theory – SciELO, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/ecos/a/qRvmZ7WbyZXGzjr3wZt7XvN/?format=pdf&lang=en

- www.imf.org, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/09/basics.htm#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20Keynesian%20economists%20would,is%20abundant%20demand%2Dside%20growth.

- Keynesian Multiplier – Overview, Components, How to Calculate, accessed October 5, 2025, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/keynesian-multiplier/

- Reading: The Multiplier Effect | Macroeconomics – Lumen Learning, accessed October 5, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-macroeconomics/chapter/reading-the-multiplier-effect/

- The Keynesian Multiplier (DP IB Economics): Revision Note – Save My Exams, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.savemyexams.com/dp/economics/ib/22/hl/revision-notes/3-macroeconomics/3-6-demand-management-fiscal-policy/the-keynesian-multiplier/

- Circular Flow of Income and the Keynesian Multiplier – The Curious Economist, accessed October 5, 2025, https://thecuriouseconomist.com/circular-flow-of-income-and-the-keynesian-multiplier/

- New Deal | Definition, History, Programs, Summary, & Facts …, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/New-Deal

- President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal | Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/franklin-delano-roosevelt-and-the-new-deal/

- Franklin D. Roosevelt: Domestic Affairs | Miller Center, accessed October 5, 2025, https://millercenter.org/president/fdroosevelt/domestic-affairs

- www.imf.org, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/09/basics.htm#:~:text=Keynesian%20economics%20dominated%20economic%20theory,appropriate%20policy%20response%20for%20stagflation.

- Post-war displacement of Keynesianism – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-war_displacement_of_Keynesianism

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monetarism#:~:text=Monetarism%20is%20an%20economic%20theory,solely%20on%20maintaining%20price%20stability.

- Monetarism – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monetarism

- What Is Monetarism? – Back to Basics – Finance & Development …, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/03/basics.htm

- Monetarism Explained: Theory, Formula, and Keynesian Comparison – Investopedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/monetarism.asp

- Quantity Theory of Money – YouTube, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q59tZKP0HME

- Quantity theory of money – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantity_theory_of_money

- Keynesianism vs Monetarism – Economics Help, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1113/concepts/keynesianism-vs-monetarism/

- Keynesian vs Classical models and policies – Economics Help, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.economicshelp.org/keynesian-vs-classical-models-and-policies/

- Graphically Taking the Quantity Equation Literally – Econbrowser, accessed October 5, 2025, https://econbrowser.com/archives/2022/06/graphically-taking-the-quantity-equation-literally

- Supply-side economics | Research Starters | EBSCO Research, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/economics/supply-side-economics

- Supply-side economics – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supply-side_economics

- Austrian school of economics – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austrian_school_of_economics

- Core Tenets of the Austrian School – Pipeliner CRM, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.pipelinersales.com/the-austrian-school-of-economics/core-tenets-of-the-austrian-school/

- What is modern monetary theory? | John Hancock Investment Mgt, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.jhinvestments.com/viewpoints/investing-basics/what-is-modern-monetary-theory

- What is Modern Monetary Theory? | Econofact, accessed October 5, 2025, https://econofact.org/what-is-modern-monetary-theory

Leave a Reply